The poetry of Thomas Albert Fox.

Among other things, on the face of it (the cyberface), this site publishes poetry held by of the Thomas Albert Fox Library. The poetry is dedicated to image-as-vision through justWords, their talk condign, befitting, rhadamantine in dark tunnels twisting, and of their loops and turns and corners and curves that tell you the sight they are seeing of their own accord along the trails of the paths set in train by Fox, where only the slither of fears guide you to follow along them hereabouts sniffing, blind to them and sightless. Here Fox defines the occidental mediaspheric global establishment and goes to earth beneath it, undermining its superfluous and superficial deceptions, its self-satisfied complacence, its conflation of novelty with creativity, of the art of surprise with the surprise of art.

In regard to 'voice', Fox persists in the use and over-use of rhyme and pun, ambiguity and picture, in conjunction with all the other 'bits' of poetic machinery. He is keen on machinery, especially the ghost of it, the ghost-in-the-machine. It is to this ghost or spirit of the poem that he looks, that which is beyond the machinery, but inextricably and inexplicably of it, that which elides into the explanatory elusiveness challenged, perhaps unsuccessfully, by Empson all those years ago. A poem's spirit is its meaning, is the right spirit, the gestaltist sum of the parts conundrum and Gottdiener's, Saussurian post-modernist machinery, that of language's diachronic and synchronic double articulation etc.

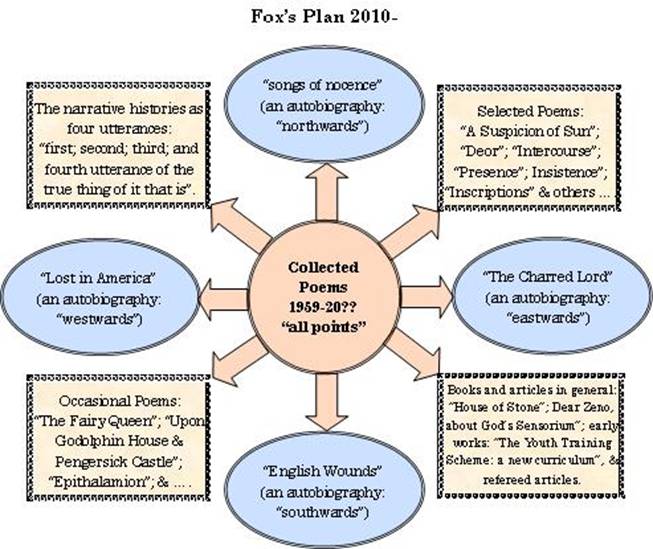

Fox's editor (me) often takes the unusual, perhaps extraordinary, step of offering these and other notes of explanation about his poems with the simple intention of helping those readers who are not crossword minded and don't mind being given more than a clue about what on earth the poet had in mind when making up the poem. The 'explanations' would not explain the 'meaning' of a particular poem, but would (somewhat semiotically) point to simple aspects of its machinery to confirm for the reader that a pun (in spite of Empson or perhaps because of him), for example, is intended, that an image is meant to be 'there', and so on, pointing the reader in the general way of the work. Fox's editor has had a close relationship with him for many years and has gleaned a lot from conversations over that time. The publication in September 2002 of "The Fairy Queen" allowed him to "explain" just one poem of Fox's, and in 2005 "Upon Godolphin House & Pengersick Castle" another, while in 2006 "Epithalamion" has allowed a third 'explanation'. "Deor: dear heart dear won" with "Core rite" was published in 2007 and illustrates the poetic process by showing in full the drafts of both poems. Also in 2007 "first utterance of the true thing of it that is" was published, but being the beginning of history, has no explanation, it being (inexplicable) work found of Albert Smith, and is the first of four volumes. In 2009 "Intercourse" was published and on 25th December 2009 "Songs of Nocence" with considerable 'explanation' of the fifteen songs encased therein, and being the first volume ("northwards") of Fox's four volume autobiography. All these contribute appropriately toward fulfilling Fox's overall plan:

All this stuff lines Fox’s lair being either completed or in draft and held in the backed up folder: “athais HP server new Z Fox Justwords”, except certain of the already published Books and Articles in General which are in hard copy only. This is the state of play after fifty years, another fifteen is needed to bring the stuff to light in a ‘complete and orderly’ way, which is, perhaps, too many to expect; but it is what the work as a whole needs, whether available or not. Obviously, this is only a matter of significance to Fox himself.

In regard to the nature of 'heris' 'explanation' of poetry, Fox is not saying any good poem can be explained except through its multi-layered whole-self as it is and becomes to those who involve themselves in it. Fox does not want to labour this point because everybody knows you can't fully 'explain' a good poem, or even a poor one; certainly you can't tell someone a good poem's meaning. This truth seems self-evident, though who would deny such as Empson being a help? So, what Fox is saying is that s/he is not one of those poets who doesn't know how his poems are constructed; you know, what the basic mechanics are, and what that machinery is up to; you know, art is just too special, too deep to be explained at all by by the maker (the artefice), that the maker is a gifted person (god given etc and some put it) and thus cannot possibly know what god was up to in the making of 'the great work' through the manipulation of an unique artistic unconscious, and such stuff and nonsense. The key to perpetuation is the provision of a key to the first vestibule of intellectual and emotional comprehension, a way into the workplace. In Fox's work this largely depends on the internal machinery (signposting) of the poetry being from itself the prime communicator, and not the literary &/or social milieu in which it sits, a milieu that is largely transitory if not merely phenomenal, that problem of simile and allusion that Ricks so ably points out in Milton.

So Fox is saying, "why don't I give the poor sod of a reader a helping hand", even though Fox knows it's just not done for the artist to explain herimself, except for schoolchildren. Well, it seems not to have been done up until now. By disturbing the status quo he's relying on the fact that most readers of poetry are intelligent in their own ways, why else would they be reading poetry, for goodness sake? So, there's little chance they'll jump to the constricting (wrong) conclusion that what his editor (me) says about any one of his poems is the last word rather than a first word. Of course, getting the first word in could be seen by some as an intimidation, rather than an intimation. Me, I think 'explaining' Fox hasn't got much chance of intimidating anyone who has chosen to become involved in his work (is anyone there?).

As you would expect, Fox's motive is purely selfish. As I understand it, he'd like to set a trend, it would save him (& me) a load of time we haven't got in a busy busy world if poets helped us into their worlds. Why not? Perhaps not quite like, as some seem to put him, poor Tom and his notes to "The Waste Land". Of course, if you have a lifetime of leisure, or a sinecure in English Lit, you could make a study of his confounded notes and write a thesis on how he has only been sending us all up, what a clever sod! Who's got time for that, we ask? Nevertheless, we discover through Christopher Ricks that Eliot himself was not actually averse to explication of this sort, in spite of impression to the contrary. And, in any case, as Ricks points out:

Sometimes a particular reader may not need the particular information, but then - as William Empson said - 'it does not require much fortitude to endure seeing what you already know in a note'. (ref xxvi)

We (Fox & me) enjoyed reading the endnotes to the Laureate poems of Ted Hughes (the poet unrelegated, at least by us). Not everyone is as bloody-minded as poor Tom; although it may be stretching credibility just a little to describe Ted as helpful. But Ted's poetry is helpful to Fox, as is, to be honest, poor Tom's too. Doesn't Fox unwittingly come back to Tom over and over and over again? He does, irritating though it is. A poet's usefulness to Fox is 'heris' very selfish way of deciding if s/he is any good (use) or not. In time, I hope to hypertext Fox's website more extensively, giving vent to many pent up endnotes and clues on (uncovering) poetic machinery. Fox's 'defence' uncovers the key ideas involved, concluding with the ludic, indeed ludicrously impossible or, more accurately, unbelievably impossible image of a between existing "in an interstice", imagine that; and when you do it (that is, you) will feel very strange indeed.

In defence of poetic machinery uncovered

]my works[

are in constant danger

that

their machinery,

the way-in to where

unaware ideas

are there-less voices

airless

unawhere

that is their uni-verse,

makes the intellectual

-ish (poetic) gatekeepers

to fields of serious con-text

and allegation of clamourous intelligence

etcetera

skid

-off the cover of the machine,

slipping and sliding over the material surface of the works,

no way-in,

no entrancing through de-composition

making-up

with the maddening rhymes

taken to their uttermost extremes

tabloidal puns dis-comfited

stretching out to their un-sensible ends

excruciatingly entangled in pursuit

of linguistic

and

imaginary ambiguity

twisted end-lessly out of meaning-less words

contradicting their semantic role

becoming only

wisps

of emotional scents

in-deference to feeling knowledge

by

imaginary fragrance of an image dimension-less

envisaged un-extracted

without ecstasy

by me

hung

un-observed

a mere semiotic strung

a final hoarding

unbelievably

dangling idiotically

between an interstice of significant sense

pointing out] [[Thomas Albert, "Intercourse", p42, voice ref 1B232]

Well, so much for the explication bit. But, poor old Fox is really trying to help save the intelligent and interested reader time and energy; but for those who are so bright that they don't need help, then they don't need to read the hypertextual notes. In fact, if they're that bright they may not need the poems, except as subjects for essays.

For example, rhyme; let me at least get that old chestnut out of the way. Yes, Fox does know that rhyme has been given up because it led poor poets into unoriginal error. Yes, and what Milton wrote is as true today as it was then (how true?). It is well worth setting out what he actually wrote fairly, so we can avoid using his rejection of "the troublesome and modern bondage of Riming" as a cunning excuse for floating around on a lazy stream of consciousness, or the stuff of deadlinitus.

...; Rime being no necessary Adjunct or true Ornament of Poem or good Verse, in longer works especially, But the Invention of a barbarous Age, to set off wretched matter and lame Meeter; grac't indeed since by the use of some modern Poets, carried away by Custom, but much to their own vexation, hindrance, and constraint, to express many things otherwise, and for the most part worse, then else they would have exprest them.

[John Milton, Preface to Paradise Lost, 1669 edition.]Even though Milton admits to rhyme being acceptable (to him) perhaps in shorter works, this is not the point. He sees rhyme as a constraint rather than an opportunity, he saw (in his own mind), of course, that he could not possibly apply rhyme to any advantage in giving voice to Paradise Lost. However, rhyme in Fox's poems are intentionally sound marriages of words and meanings. The rhyme of sound always has concomitance of meaning, as in his poem about rhyme in time; such concomitance is often complex and not always obvious; for example the internal (core) rhyming of "grammar", "clamour" and "glamour", may begin to tell more when the derivation of glamour with grammar is imbued with all the other aspects of the poem and its soundings out.

Now isn't this world a perfect place

In which to make that special case

With words that fleet without a trace

Beyond the glitter of pure disgrace

Surfacing over its slippery face

Where you feel them grin and grimace

A moving grammar of empty space

And in the clamour of their embrace

Confusing glamour with signs of grace

Casting light upon a human race

That ever circles at its daily pace

The pointless point that is its base.[A rhyme in time is not a crime, Thomas Albert Fox, "Intercourse" p35, Voice ref 1A590]

Fox's Gerry Adams poem is a good case in point, even to the internal rhyme "huddled" with "muddled". Is there not a certain telling justice to "conspire" with "perspire" (the effect on tv); "deadest end" with "message send"; "unfeigned" with "is gained", and the internal literality of the lines, referenced as they are to the true meaning of Sinn Fein ("we ourselves") ; and then there is the ghastly justice of "arms upraised" with "silence praised". He would not publish "Inscriptions" as such (or "English Wounds") without at least completing certain further poems to ensure the volume reaches beyond the merely partisan. To do so would be to invite the usual paltry accusations of bias against the poor, hard done by Irish terrorists whatever their ilk; generating even more misunderstanding than will follow any publication of poems which go to the empty heart of these murderous fascists. Such murderers typify the inevitable fascist tendency in all human societies past, present and future when a self-selected clique decide their opinions and self-interests are so important that they are entitled to apply the ultimate injustice (their end makes it worth it for them): to deliberately take aim at the life of others and to kill, or to manipulate others to this end, in the name of their own self importance gleamed and polished in the sweats of injustices they feel they have suffered (usually vicariously). Now Fox has the "Casement", "McGuinness", "Paisley" poems there is a better, if bitter, justice in "Inscriptions" as a whole.

Of course, in recent times (since 11th September 2001) Adams has slid like a snake into the new skin of a peaceful democratic coil, insinuating the National Socialism of Sinn Fein (SF) along with him. Plausible as ever, sly and opportunistic, he has presented himself since 9/11 as the one person struggling against all the violence. On 21st October 2002 he announced that the death ("end") of the IRA was "possible", that the future could do without their murderous criminality. Indeed, Adams simply concedes the inevitable: that his ace in the hole, bombing London and other English city centres, is no longer a deployable option since 9/11. It didn't take long for Americans to convert the city centre bombing of the Twin Towers and the mass murder of 3,000 people into a convenience store for news entertainers and other trashocracies the world over (9/11). Neither did it take Ireland's leading National Socialists long to work out that the days of the IRA as an effective private terrorist resource of their own were over. The IRA became almost overnight that awkward liability, continuing a major but plainly undeployable weapon. Sadly, the Unionists realised all this too and took the opportunity to scupper the Easter 2000 peace terms. Their brutal logic seems that they need not stomach its terms now 9/11 has emasculated the IRA, and anyway they'd mostly not accepted the terms or only under duress. Thus, David Trimble is dumpable through a new election likely to give the DUP and SF new mandates to do their worst, putting the whole Irish mess up for re-negotiation in the shadow of the twin towers and the dead of the (Irish) Fire Services in New York. Ian Paisley comes to the fore, and we are faced with the spectacle of Paisley and Adams making it to the top as joint leaders of the province. Unfortunately, the IRA's members, the common criminals, the uncommon psychopaths, the crackpot ideologists, and other misfits, trained in terrorist techniques (ie how to butcher &/or bludgeon men, women and children with impunity) are not likely to simply disappear up their own backsides, but seem set to continue to lurk like rats among the open sewers containing their foul deeds, waiting to be put down by a new pest control system, while eyeing the King & Queen Rats of Sinn Fein with some malevolence.

Even the apparently silly rhymes in the Jimmy Carter poem are literally apt. To "think" too much while you are on your feet will cause you to "blink" giving away your real position amongst each "nod and wink" of practical negotiations. Such weaknesses in Carter were a greater danger to world peace than tough professional negotiation. However, it enabled the "Nobelity" to award him a the "Peace Prize" in 2002, a kind of consolation or booby prize presumably for being a nice loser. Jack Kennedy (also brutally rhymed) was nice to Kruschev in Vienna 1961 and that led to Kruschev trying it on in Cuba in 1962, a very close run thing opening the world to mass destruction on a mischance of a few words that luckily (yes, luckily) didn't get muddled or miscarried. Hear how the rhymes in the Nixon poem lead to another kind of justice. Mostly Fox's rhymes are very clear in what they are up to; but don't overlook the apparent wrenching of "war" to "door" when you consider why this rhyme has much more to do with the complex and violent trade off between Vietnam, China and the USA for a world statesman, or even if you are not a world statesman and just a tricky bastard.

All this pitifully manipulative malevolence pales at the prospect of Islamic extremists dirty bombing London in keeping with their perverted love of a new God invented by them to vent their gratuitous hatred of "The West" and its freedom to explore the extremes of human deviance. Of course, the majority of Muslims disavow such a God, and stick to their own apologetics and subtle transfer of culpability from their extremists to "The West" and its non-Muslim behaviour. Such ambivalence is typified by the problem of the hijab as mask, and mask as both a (dishonest) hiding and a flag. Fox, the inveterate atheist, has characteristically considered this issue with his "Veiled Threat: or Dance of the Seven Sonnets", another rhyming thing expressing his concern to protect tolerance of the behaviour of others which is reasonable and not seriously harmful to others.

A Veiled Threat:

Dance of the Seven Stanzas1

Barefaced behind its veil

Modesty told its tale

Of blackened name

Of biased blameIts little voice so sweet yet strong

Explaining that it’s very wrong

To complain of hoods and masks

And blackness draping all its tasks

Covering up its flesh and face

Hiding half the human race

To keep it modest by any means

In its place behind the scenes

Safe from any passing male

Whose naked eyes see right through a veil

Whose strip reveals their open eyes

Captivating with their tearful cries

Getting all within their grip

As they dance naked through the strip2

Barefaced behind its beard

It was something rather weird

Of bristling chin

Of broiling sinPassing over its hirsute grin

Assuming serious thoughts within

It seemed to know how to behave

Without the need for it to shave

Its throaty voice that drew so deep

Spoke of freedoms fast asleep

As if through sickness they’d been hurled

To wake upon a brand new world

To find those freedoms had been drained

By love so free and unrestrained

That it fell through all its choices

With no account for childish voices

Crying of those acts distorted

To say true love had been aborted3

Barefaced behind its paint

Appearing simply quaint

Of worldly show

Of farded woeMaking up its lovely hints

Displaying nothing but its tints

An armour shielding naked flesh

Beguiling layers that enmesh

In common fashion to conceal

What their faces could reveal

Their painted skin so full of lies

The very meat of their disguise

In their eyes there is no crime

To make their faces seem sublime

As worldly clowns who cannot see

The part they play is not to be

For as they make up for their parts

They find they’ve painted out their hearts4

Barefaced behind its woad

It spoke a savage code

Of fearful race

Of frightful faceHot as mustard they quickly dyed

Facing any other side

Up they’d rise a maddened tribe

In the face of any jibe

They’d give no sign of being weak

When they showed their other cheek

For in their face was how they spoke

Speaking through a wordless cloak

Woven of the dreadful dye

Painted to deceive the eye

It’s all depiction in their sight

To create appalling fright

While all along the tribal front

Hatreds form in packs to hunt5

Barefaced behind its colour

It played upon its power

Of separate shades

Of different gradesIn black and brown and yellow and white

They face the world in sight

For all they see is deep as skin

Yet in their eyes they are not kin

But split by hatreds to pursue

The slightest difference in their hue

Disliking people is the game

As if they are not all the same

Except that each one is unique

Not standing out as just a freak

But washed all over by the light

To bring them plainly into sight

Where they must stand just as they are

Beyond that gruesome colour bar6

Barefaced behind its cloth

Brewing up its broth

Of hoodies slunk

Of holy bunkThe closeted worldly oyster

Hid inside its shady cloister

Whose succulent face seems so replete

Treating itself to secret meat

Well tucked beneath its hood

Where it’s barely understood

Enclosing flesh inside its cloak

That could become an open joke

Rounded as a bell out of the press

A ringing show of wantoness

For it told the age old tale

Of indulgence gone to hell

But there is nothing so extreme

They cannot pardon like a dream7

Barefaced beneath its skin

It seemed so terribly thin

Of creasy facts

Of papered cracksCovered up by powders and creams

Is this face so full of seams

That it can never face the truth

Of seeing itself as final proof

That the person is the masque

Which is like an empty cask

Containing nothing but its form

That empty eye within a storm

Appearing as if it were a being

That was truly really seeing

But who could countenance such a blinding sight

Stare into the brilliant light

Seeing through those human veils

To see those prisoners in their jails?[Thomas Albert Fox, "Intercourse", p99].

NOTES: This poem is taken from: Thomas Albert Fox, “A Veiled Threat: Dance of the Seven Sonnets”, 2006, in “Intercourse”, published in 2008, and included in the notes published with "Epithalamion Upon the Wedding of George Mihov and Malvina Kotorova Upon this the Sixteenth Day of September 2006CE", justWords 14th November 2006. The poem is structured upon the Dance of the Seven Veils as a metaphor for the various unveilings of human being as disclosed by the multifaceted aspects each being chooses, wittingly or unwittingly, to present through their outward appearance. It is known more commonly as NVC, non-verbal communication. The seventh stanza is the seventh veil which can only reveal that naked skinless flesh is formless, is without edge, therefore shapeless, and thus wholly unrevealing. It is only through disguising veils that such formless flesh is made solid. In general, the deployment of the pronominal gender is significant. Neuter “it” is used to weave an indication of the seeming anonymity of the being (initially) claimed by each stanza as uttering its meanings. There are various particular references throughout, for example in stanza 6 (lines 13-14) that to Geoffrey Chaucer’s General Prologue portraying “The Friar” (lines 55-58):

Of double worsted was his semicope,

That rounded as a belle out of the presse.

Somewhat he lisped, for his wontonesse,

To make his Englisse sweete upon his tonge.Stanza one references the Jack Straw (Leader of the British House of Commons) and the Aishah Azmi case in the UK, October 2006, of silly politician insisting we shave our beards, or was it remove our veils (?) when going to see him, this to counter the veil as a gratuitous display of piety taken to an absurd if mischievous political extreme. Rhythm is used in a very controlled way throughout the seven stanzas, for example to heighten attention in Stanza one, line 14, to bring out the pun on “right”. Stanza two references Blake’s “Oh, Rose Thou Art Sick …”. Stanza three (line 12) references an Australian Muslim cleric’s accusation that women without a veil are “uncovered meat” (26th October 2006 Sydney, Australia, Sheik Taj Aldin al Hilali). Stanza three, line 4 “farded”, the white face paint used by clowns. “Quaint” is (also) a Shakespearean pun on cunt. Stanza four plays on mustard and woad (blue dye from a mustard plant much favoured by warlike Celtic forbears). Stanza seven extends cask to involve its helmet etymology. While “person” is contradistinguished with “masque”, as both mask and play, and by the modern use of “person” to imply personality as unconsciously constructed individuality through display of a persona (L mask). Essentially, the rhetoric of the stanza proposes that people are at once the masters (or mistresses) and slaves of their outward appearance. Thus, what they are is what makes them what they are. (And so on). In the end, as it were, such rhyme as veil and jail sound like natural truth. Fox pursues severally the idea of the perfect rhyme conjoining being in time, a strong example of such philosophical management of 'being' is "Sunset Waltz" (p88, "Intercourse"), and one song of fifteen in "Songs of Nocence" (as "Sunset Song"), published in 2008:

We sit together on our own

Seeing how the sun goes down

Feeling that our time has flown

But knowing we have closer grown

And dance among these sunset rays

Toward the ending of our days

And neither of us would be loath

If the sun would draw us both

Into that world of light unknown

So neither one was left alone

We would fly there hand in hand

To stay forever in that land

In which our lives would be enshrined

By perfect light that always shinedNow our flight on wings of guile

Seems to let us sit a while

In that land where all is bright

Just beyond our normal sight

Where our time we wile away

To keep the rush of time at bay

As if it were the only place

Where our rhythm has no pace

And we could fix ourselves in space

With nothing of our human case

So all our lives would freeze in time

And seize us as a perfect rhyme

Keeps us at the end of time

And sees one as a perfect rhymeSo much for "explaining" rhyme. I'm leaving out reference to half rhyme or pararhyme which Fox likes a lot, and is (of course) rhyme too. Well, perhaps I could just say that when mimicking, for example ottava rima, there is a natural pressure to solve the "hindrance" of rhyme by resorting to pararhyme; but very great care is needed to ensure that the natural general effect of such incompletion, such frustration in the marriage is the required ambient feeling. Fox's Ion Bitzan sonnet is a good example of what I regard as an ideal use of "half completed rhyme" (eg time and tome), leaving aside the play on "facts" for Bitzan and the idea of electronic "world"; there is also reference to Bitzan as Solomon and the dividing of the child which refers to his work on the biblical Song of Solomon, and, in a broader context, to his treatment of book-as-object in "Fax For Bitzan":

Dearest Ion, from your place to mine

Seemed only a matter of space and time,

Mere coordinates one has to have in mind

To send such facts between two worlds so oddly cleft

Where one and one make three with nothing left,

And every note cannot be seen, but line by line

They lay their fatal strain wherein I heard a wise man sing,

And undivided like a child I looked and saw his sign

Which showed the end of words was like a half completed rhyme

That echoes on and on until the end of time

To find its final home in some god or other's mighty tome

Wherein it sits bereft in mime;

Just brought to book a shape of purest truth

Whose thoughts escape like kisses from his mouth.

(Bitzan, Ion 1924-97, Solomon, Volume 2 "Inscriptions", page 6, Voice ref 1A238)I'm also leaving out reference to Fox's essential use of alliteration; essential, nay quintessential, to any poet who is English. And it is the way back to the world when the poet's voice was word of mouth, or should I say a mouth of words? "The Mouthing". The disruptive nature of Fox's work can be further observed in his utterances under the name of Alfred Smith. While consideration of this bloomer will also help.

flower

floorflour

flow er

Say if you want a short one, or long or in between, a nice one, a hard one, one you couldn't possibly accept, or a completely off-the-wack-one. Or say your own way of it what kind you want. The T A Fox library is owned by justWords Ltd. It holds all ten volumes already published and all work in draft and the rights to pick and publish whichever. Fox himself, although not quite dead, has been laid to indiscriminate earth and can't say a word, except earth, his mouth full of it, poor sod. Fox will only answer questions put to him in writing, after all he is a writer and not an oratorial debater.

Although Fox's work does not fit into a genealogy of postmodern poetry, you may still find it a help dealing with the edges of his work, if not the core, to read Albert Gelpi's 1990 paper "The Genealogy of Post Modernism: Contemporary American Poetry". Gelpi is very interesting generally, and openly accessible at University of Pennsylvania's valuable contribution to the net (which is what matters if you don't have access to the resources of a university as a member of staff).